Alcohol brief intervention has a small but significant effect on 12-month drinking outcomes in an integrated healthcare system

Alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment, also known as SBIRT, is an evidence-based intervention when delivered in adult primary care settings to address unhealthy alcohol use. However, real-world evidence for this intervention and its different components is lacking. In this study, researchers examined the implementation of systematically delivering alcohol brief intervention in a large healthcare system among adults with unhealthy alcohol use.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Unhealthy alcohol use presents an immense burden to society and this burden is increasing over time. In the United States, the number of alcohol-related deaths per year doubled from 1999 to 2017, with more than 72,000 of these deaths in 2017. Alcohol-related deaths continued to increase during the COVID-19 pandemic, with nearly 100,000 deaths occurring in 2020. In addition to mortality, the economic impact of unhealthy alcohol use is estimated to be around $250 billion. Despite the public health burden of alcohol use disorder and other forms of unhealthy drinking, the vast majority of people with an alcohol use disorder do not receive treatment. Recent evidence suggests that of the almost 8% of American adults with a current alcohol use disorder, only 6% of these individuals receive treatment and, while 70% are screened for unhealthy alcohol use, only 12% report receiving a brief intervention and 5% are referred to treatment.

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (also known as SBIRT and pronounced “esburt”) is an evidence-based intervention for addressing unhealthy alcohol use among adults and is recommended by the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force in primary care settings. This intervention has potential for early intervention of risky drinking as well as identifying and linking cases of alcohol use disorder to treatment. There is a spectrum of unhealthy alcohol use from risky use to alcohol use disorder including alcohol addiction, and SBIRT is broken up into different components to address these different levels. For example, if SBIRT were implemented in a primary care office, everyone would be screened for unhealthy alcohol use, positive screens for high-risk alcohol use would receive a brief intervention, and positive screens for severe alcohol use would be referred to treatment. Despite the evidence for SBIRT, there are challenges implementing it in clinical settings, so how helpful this intervention is when implemented in an actual healthcare setting is still not clear (i.e., the “real-world” effectiveness of the intervention). In this study, researchers examined the impact of systematically delivering SBIRT to adults in primary care settings in a large healthcare system, with a particular focus on the impact of the brief intervention component on drinking outcomes 1 year after the intervention was delivered.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study used longitudinal electronic health record data to measure the impact of a brief intervention delivered to adults in primary care who screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use on drinking outcomes 12 months later.

The study setting was a large and integrated healthcare system (Kaiser Permanente Northern California), which includes over 4 million members in the region with a patient population representing both public and private health insurances. The SBIRT intervention was implemented into the adult primary care workflow to provide systematic screening for unhealthy alcohol use. A screening instrument developed by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) was administered by a medical assistant to each adult at the primary care visit. Drinking that exceeds the maximum recommended daily limits (>3 drinks/day for women and men aged >65 or >4 drinks per day for men aged 18-65) or weekly limits (>7 drinks/week for women and men aged >65 and >14 drinks/week for men aged 18-65) were considered positive for unhealthy alcohol use. Per protocol, if positive, the physician conducted an alcohol brief intervention with the patient based on Motivational Interviewing principles and provided a referral to addiction medicine if appropriate. In other words, all positive screens should have received an alcohol brief intervention per the healthcare system’s protocol for SBIRT.

Patients are screened annually in this large healthcare system. From 2014 to 2017, 440,882 patients screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use. After removing patients who did not have continuous membership in the healthcare system in the prior year, were over 85 years old, or did not have complete alcohol screening results, the final analytical sample included 312,056 patients among 3,180 clinical providers.

The variable of interest among these 312,056 patients was receiving an alcohol brief intervention. This was measured using the 9th and 10th editions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9 and ICD-10) codes in the electronic medical record. Among patients that screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use, those that received the alcohol brief intervention were compared to those who did not receive this intervention. In other words, the former served as the treatment group and the latter served as the control group. The study did not mention specific reasons as to why someone might not receive the alcohol brief intervention after a positive screen. In addition, patients were classified into mutually exclusive groups capturing alcohol use patterns based on their answers in the initial screening (also known as the index date): “exceeding only daily limit”, “exceeding only weekly limit”, and “exceeding both daily and weekly limits”. As a secondary analysis, this study also looked at the impact of receiving specialty treatment for alcohol use disorder on 12-month drinking outcomes and this was defined as having 1 or more outpatient visits or receiving pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder.

Four alcohol-related drinking outcomes were measured between 7 and 12 months after the alcohol brief intervention. These included:

- Change between index date and the 12-month follow-up in the number of heavy drinking days in the past 3 months (“heavy drinking”) – heavy drinking days were defined as 5 or more drinks in a day for men aged 18-65 and 4 or more drinks in a day for women and men aged >65

- Change between index date and the 12-month follow-up in the number of drinking days per week (“drinking frequency”)

- Change between index date and the 12-month follow-up in the number of drinks per drinking day (“drinking intensity”)

- Change between index date and the 12-month follow-up in the number of drinks per week (“total consumption”)

Patient and provider characteristics were extracted from the electronic health record at the index date. Patient characteristics included sex, age, race/ethnicity, insurance type, socioeconomic status (using neighborhood deprivation index as a proxy), body mass index, self-reported physical activity, smoking status, physical comorbidities (measured by the Charlson comorbidity index), and a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder, drug use disorder, or mental health condition in the past year.

Clinical provider characteristics included age, sex, race/ethnicity, specialty (Internal Medicine, Family Practice, or Other), and years of service. In analyzing this data, researchers employed a statistical technique (called marginal structural models with inverse probability weighting) to make the treatment group (individuals who screened positive for unhealth alcohol use and received alcohol brief intervention) and the control group (individuals who screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use and did not receive alcohol brief intervention) more similar, in an attempt to minimize bias given that the patients were not randomly assigned to receive the brief intervention or not but were selected from existing clinical records. Provider characteristics were also included when using this statistical technique to minimize provider discretion in delivering the brief intervention to those who screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use. Interaction terms were used in the statistical analysis models to explore whether the effect of the alcohol brief intervention on 12-month drinking outcomes differed by patient characteristics.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Only around half of individuals who screened positive actually received the alcohol brief intervention.

Only 48% of the 312,056 eligible patients who screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use received the alcohol brief intervention even though all patients screening positive should have received this intervention. Those who received the alcohol brief intervention (i.e., the treatment group) were compared to those who did not receive the intervention (i.e., the control group). All patient demographic and clinical characteristics examined were significantly different between these 2 groups.

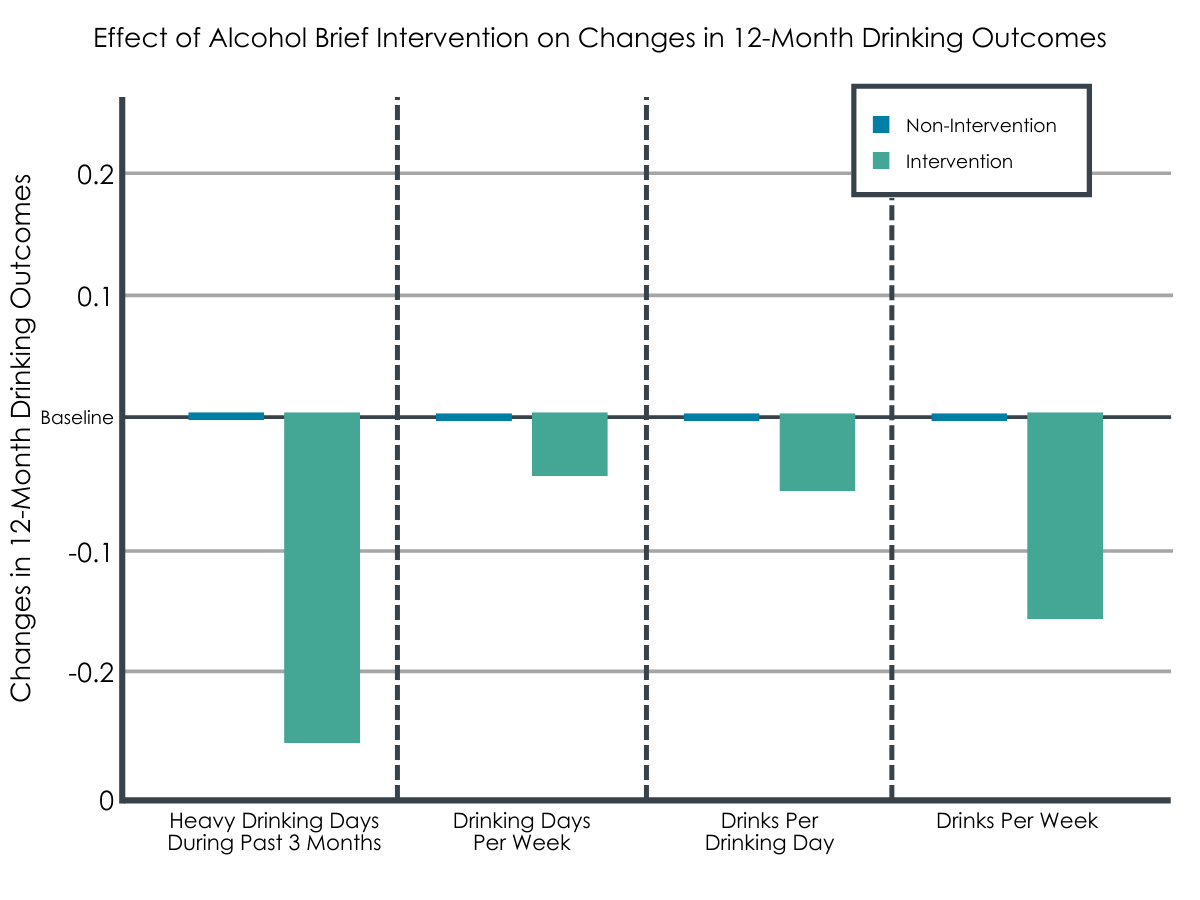

There was a small but significant effect of alcohol brief intervention on reducing 12-month drinking outcomes.

Receiving the alcohol brief intervention reduced all 4 drinking outcomes after 1 year. The effects were small but statistically significant and were measured by mean differences. The effect sizes (i.e., change between drinking outcomes at the index date and the 12-month follow-up visit) of the alcohol brief intervention were a 0.26 reduction in heavy drinking days during the past 3 months, a 0.04 reduction in drinking days per week, a 0.05 reduction in drinks per drinking day, and a 0.16 reduction in drinks per week.

Some patient characteristics predicted better 12-month drinking outcomes.

The effect of the alcohol brief intervention differed by alcohol use patterns. Receipt of the intervention was associated with greater reduction in heavy drinking days among patients who exceeded only daily drinking limits (i.e., 4+ for women and men 66 and older and 5+ for men 65 and younger) and those who exceeded both daily and weekly limits (i.e., 7 weekly drinks for women and men 66 and older and 14 for men 65 and younger). Receipt of the intervention was associated with increased heavy drinking days among patients who only exceeded the weekly limit. Also, receipt of the alcohol brief intervention resulted in a slightly greater reduction in drinks per drinking day among patients exceeding only daily drinking limits with no effect for the other 2 alcohol use pattern groups.

The effect associated with the alcohol brief intervention was slightly larger among younger patients. Those aged 18-24 and 25-34 had a further reduction of -0.18 and -0.07 drinks per drinking day at 12 months respectively, and those aged 65 and older had an additional 0.04 drinks per drinking day increase. Also, having an alcohol use disorder diagnosis in the year prior to the positive screening made it less likely that the alcohol brief intervention helped reduce alcohol use when measured at 12-months.

Receiving specialty treatment was associated with reduced 12-month drinking outcomes.

As expected, receiving specialty treatment for alcohol use disorder reduced all of the 12-month drinking outcomes irrespective of receiving SBIRT, and the effect sizes were much larger compared to the alcohol brief intervention. Receiving treatment resulted in a 3.20-day reduction in heavy drinking days during the past 3 months, a 0.83-day reduction in drinking days per week, a 0.59 drink reduction in drinks per drinking day, and a 4.21 drink reduction in drinks per week.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The study found small but significant reductions in all 4 drinking outcomes measured when a brief intervention was delivered to adults who screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use in a large and integrated healthcare system in Northern California, with better improvements for younger adults, those without a previous history of alcohol use disorder, and those who were drinking at levels exceeding only daily (but not weekly) NIAAA-defined limits.

Findings from this study suggest that real-world implementation of a systematic screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) model in primary care settings of a large and integrated healthcare system is associated with small, but statistically significant, reductions in all 4 drinking outcomes measured. Given the short time needed to deliver the brief intervention, its low cost, and the potential to improve patient health, it is likely that implementing this model is cost-effective and could be helpful in the continuum of addressing unhealthy alcohol use. This is especially relevant given that the alcohol treatment system in the United States is geared towards the most severe cases and the vast majority of Americans with alcohol use disorder do not receive any treatment, primarily because they do not perceive a need for treatment. Therefore, SBIRT, and the brief intervention component specifically, has the potential to raise awareness of unhealthy alcohol use early on and prevent progression to alcohol use disorder. There are also emerging technologies to help streamline implementation of this model that could address challenges and make it even more helpful in the future.

Importantly, the study also found that patients with a positive screen who had a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder in the previous year did not show much improvement, consistent with recommendations that those with alcohol use disorder are likely to need higher-intensity interventions, and results were identical whether the researchers controlled for receipt of treatment or not in their model. Other research has highlighted that, although brief interventions may benefit those with risky alcohol use but without alcohol use disorder, there are limitations of a brief intervention for those with alcohol use disorder, especially in linking those to treatment who need it. Also, although the brief intervention had a positive overall impact on drinking outcomes, younger adults experienced a further reduction in these outcomes suggesting that this population could benefit from brief intervention especially if their at-risk drinking is not too severe, in line with other research.

In addition to improving patient health, implementing the SBIRT model has the potential to improve public health outcomes at the population level. This could be optimized by increasing the number of people who screen positive, in fact, receiving a brief intervention. Only around half received the brief intervention in this study whereas protocol called for everyone who screened positive to receive the intervention. Implementation of this model in another very large healthcare system showed that a little more than a quarter of people who should have received a brief intervention actually received it, and, while 70% of American adults with alcohol use disorder are screened for unhealthy alcohol use, only 12% reported receiving a brief intervention. Notably, the highly integrated healthcare system in this study is very different than the fragmented healthcare system that is typical across the United States. More research is needed into the implementation challenges of this potentially helpful model.

Only half of patients who screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use received the brief intervention despite the protocol that all patients who screened positive should receive the brief intervention, and patients who received this intervention were different from patients who did not receive this intervention across a range of patient characteristics. In addition to being a significant limitation to analyzing the data in this study, provider discretion could be further explored to better understand the decision-making process of delivering the brief intervention. For example, clinical burden, limited resources, medical oversight, and lack of behavioral health providers to support referrals to treatment could all be reasons why a provider did not deliver an alcohol brief intervention to someone who screened positive. Also, people with an alcohol use disorder were less likely to receive the alcohol brief intervention, possibly meaning that their alcohol use problems were so severe that the provider referred to specialty treatment without delivering the alcohol brief intervention.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This study likely had significant bias since it was a non-randomized study comparing a group who received an alcohol brief intervention with a group who did not receive an alcohol brief intervention among a cohort of people who screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use. About half received the intervention although all patients should have received the intervention by protocol. Therefore, provider discretion, which is difficult to measure using an electronic health record, likely played a significant role in deciding whether to deliver the intervention or not. Researchers tried to minimize this limitation using advanced statistical techniques, but this is not a substitute for randomized designs.

- Even though these results were from a large healthcare system serving over 4 million people, generalizing these results should be done with caution, especially since the study setting was in an integrated healthcare system unlike most other healthcare systems in the United States and is localized to 1 region of the United States.

- It is unclear if the small effects of alcohol brief intervention on reducing 12-month drinking outcomes are sustainable beyond 1 year. More research is needed especially to understand which groups of individuals in particular might be more responsive to these kinds of interventions and which are not.

- Given the very large sample size, it is also unclear if these small but statistically significant average effects are clinically meaningful. More research is needed on downstream outcomes, such as alcohol-related morbidity and mortality measures.

- The current study could not evaluate linkages between alcohol screening, brief intervention, and receipt of specialty treatment because patients served by this comprehensive healthcare system do not need a referral for specialty alcohol use disorder treatment.

BOTTOM LINE

This study used electronic health record data to measure the association between receipt of a brief alcohol intervention delivered to adults in primary care who screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use and their drinking outcomes 12 months later. The study found small but statistically significant reductions in all 4 drinking outcomes measured, with slightly better improvements for younger adults, those without a previous history of alcohol use disorder, and those who were drinking at levels exceeding only daily (reflective of more intensive hazardous use), but not weekly (reflective of greater toxicity-related effects related to overall alcohol exposure over time, such as increased chronic burden on the liver and increased alcohol-related cancer risks), NIAAA-defined guidelines for non-risky drinking.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) is a method of quickly screening for unhealthy alcohol use, providing a motivationally based brief intervention for positive screens, and providing referrals to specialty treatment as needed. This model is commonly implemented in primary care settings for adults, and there is strong evidence that it helps improve risky drinking, especially among those who have not developed an alcohol use disorder. While more intensive treatment is recommended for moderate to severe cases of alcohol use disorder, according to this study even a single session of alcohol brief intervention may be associated with reductions in risky drinking outcomes after 1 year.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: These study findings add to the evidence that the brief intervention component of SBIRT is helpful in reducing risky drinking, with a modest effect seen in this study on reducing 12-month drinking outcomes including heavy drinking days, drinking days per week, drinks per day, and drinks per week. Although it is unclear how clinically meaningful these small reductions are, delivering brief interventions to individuals screening positive for unhealthy alcohol use has the potential to raise awareness of this risky behavior early on and possibly prevent progression to alcohol use disorder. At a broader level (e.g., across a treatment system or a country), even small improvements in drinking outcomes can make a difference at a population level. While more intensive treatment is recommended for moderate to severe cases of alcohol use disorder, according to this study even a single session of brief intervention may be associated with reductions in risky drinking outcomes after 1 year, especially among younger adults and those with unhealthy alcohol use but no alcohol use disorder. Widespread adoption could increase the impact of the SBIRT model.

- For scientists: This study examines a real-world implementation of SBIRT in a large and integrated healthcare system. More research is needed to better understand SBIRT generally and the results of this study specifically. The findings were on average very small but statistically significant and may not be clinically meaningful. Studies looking at more downstream public health outcomes, such as alcohol-related morbidity and mortality, are needed as well as studies that look to see if the effect is sustained beyond 1 year, and who is more or less likely to respond to these types of brief interventions. Implementation of SBIRT is challenging and the healthcare system setting used in this study is unique. Future studies should look at how this integrated healthcare system may be better suited to implement this systematic model. Linkage between brief intervention, referral to treatment, and treatment utilization could not be examined by this study, and future studies should explore how this linkage of the components of SBIRT impact outcomes. Studies are also warranted on the “population-health” impact of the widespread adoption of the SBIRT model.

- For policy makers: Alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) is a method of quickly screening for unhealthy alcohol use, providing a motivationally based brief intervention for positive screens, and providing referrals to specialty treatment as needed. This model is commonly implemented in primary care settings for adults, and there is strong evidence that it helps improve risky drinking, especially among those who have not developed an alcohol use disorder. There is also evidence that this intervention is cost-effective. While more intensive treatment is recommended for moderate to severe cases of alcohol use disorder, according to this study even a single session of brief intervention may be associated with reductions in risky drinking outcomes after 1 year. Therefore, this model may be helpful in addressing the spectrum of unhealthy alcohol use. There may be a particular benefit in intervening early in people exhibiting risky drinking but not alcohol use disorder given that the vast majority of people who ultimately develop alcohol use disorder will not receive treatment.

CITATIONS

Chi, F.W., Parthasarathy, S., Palzes, V.A., Kline-Simon, A.H., Metz, V.E., Weisner, C., Satre, D.D., Campbell, C.I., Elson, J., Ross, T.B., Lu, Y., Sterling, S.A. (2022). Alcohol brief intervention, specialty treatment and drinking outcomes at 12 months: Results from a systematic alcohol screening and brief intervention initiative in adult primary care. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 235, 109458. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109458