Access to fun activities is known to protect against substance use among people at risk addiction. This study explored how access to fun activities might also be protective in early recovery.

Access to fun activities is known to protect against substance use among people at risk addiction. This study explored how access to fun activities might also be protective in early recovery.

l

Alcohol and other drugs produce effects that are rewarding to the individual taking them. Not surprisingly, the rewarding nature of alcohol and other drugs is amplified when individuals’ lack alternative rewarding activities. Conversely, people with greater access to rewarding, fun activities are less likely to develop substance use disorders and related problems.

In theory, access to rewarding, fun activities would also be protective in people engaged in treatment for substance use disorder. This fits with contemporary theories of addiction recovery that recognize the importance of recovery capital – the sum of tangible and intangible resources available to an individual. It also fits with research showing the importance of changes in social networks from pro-substance-using to pro-recovery peers, which is likely also associated with greater access to pleasurable activities not involving alcohol and other drugs. Thus, access to fun activities may support substance use disorder recovery, yet its influence on recovery outcomes has not been well studied.

In this study, researchers explored how access to fun activities, and the enjoyment derived from them, is associated with substance use outcomes and life satisfaction in a large sample of people in treatment for substance use disorder.

This was an observational study of 5,481 individuals who had recently completed treatment for substance use disorder and were assessed 30 days following treatment discharge to explore associations between access to fun activities and return to substance use and life satisfaction.

Data were collected using a web-based platform delivered via email or text message, with participants asked to characterize their past 30 days since leaving treatment. Measures included: 1) Time (hours per week) spent in fun activities versus substance use related activities; 2) Access to fun activities (on a scale from 1-6); 3) Enjoyability of fun activities (on a scale from 1-6).

The primary study outcomes measured for the 30 days following treatment discharge were: 1) Return to any substance use, including any alcohol or other drugs (yes or no); and 2) perceived life satisfaction (on a scale of 1-10). Study participants identified their primary drug at treatment intake.

The study sample was 62% male, 37% female, and <1% Other. The majority of participants were White (85%), with individuals identifying as African American (7%), Native American (1%), Asian (1%), and Other (5%) also represented, but to a much lesser degree.

Access to, and enjoyability of fun activities varied by primary substance

Participants whose primary substance was alcohol had the greatest time spent in fun activities relative to time spent in substance use related activities. This was in contrast to participants whose primary substance was benzodiazepines, cocaine, heroin, marijuana, methamphetamine, prescription opioids, or prescription stimulants.

In terms of access to fun activities, participants reporting methamphetamine as primary reported less access relative to participants whose primary substance was alcohol. Additionally, when just considering the 1,369 participants who had returned to substance use over the assessment period, those whose primary substances were either methamphetamine or heroin reported less access to fun activities relative to those for whom alcohol was primary, with medium-sized differences. Specifically, in this sub-sample who returned to any use, heroin-primary individuals had 60% of their free time spent on fun activities versus 75% of alcohol-primary individuals.

There were also differences in terms of enjoyment of fun activities. Relative to participants whose primary substance was alcohol, participants reporting marijuana or methamphetamine as primary reported less enjoyment of fun activities. And among participants who had returned to substance use, those whose primary substances were either methamphetamine or heroin reported less enjoyment of fun activities relative to those for whom alcohol was primary.

Greater access to, and enjoyability of, fun activities associated with lower chance of substance use

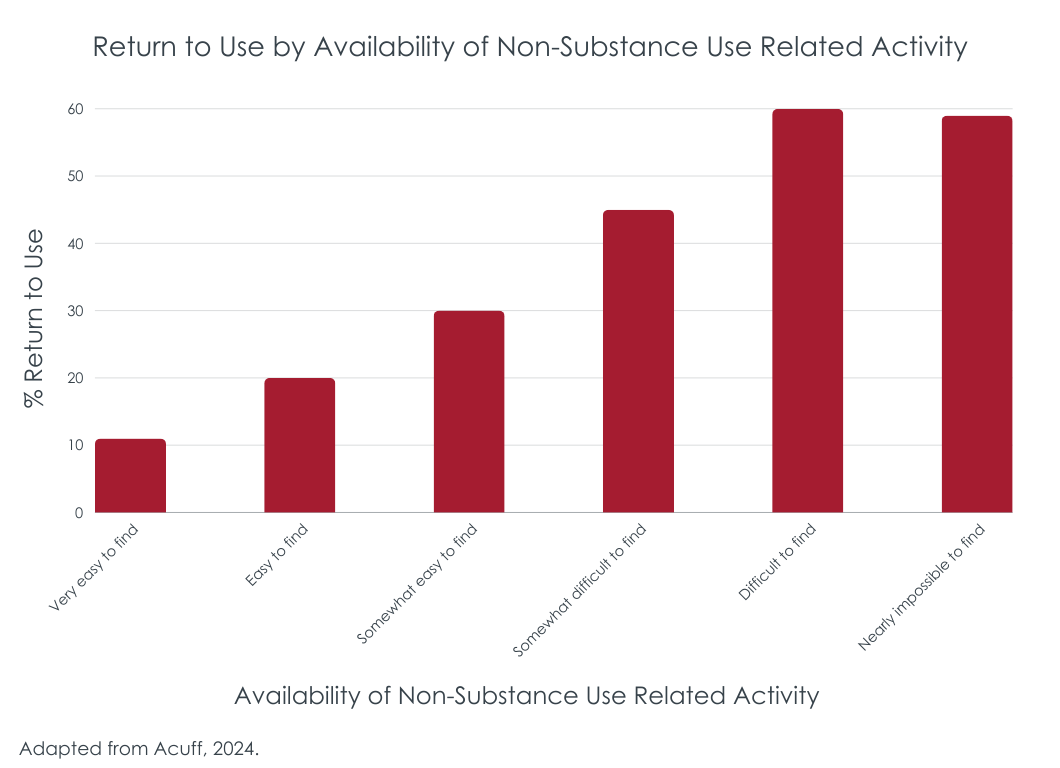

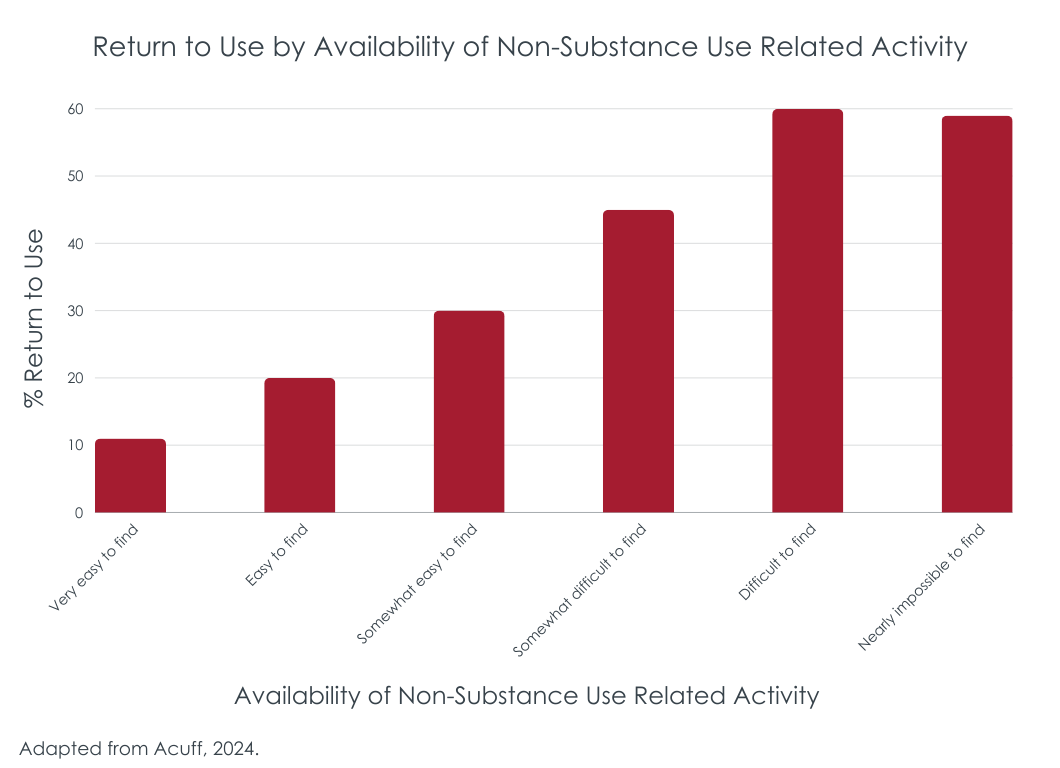

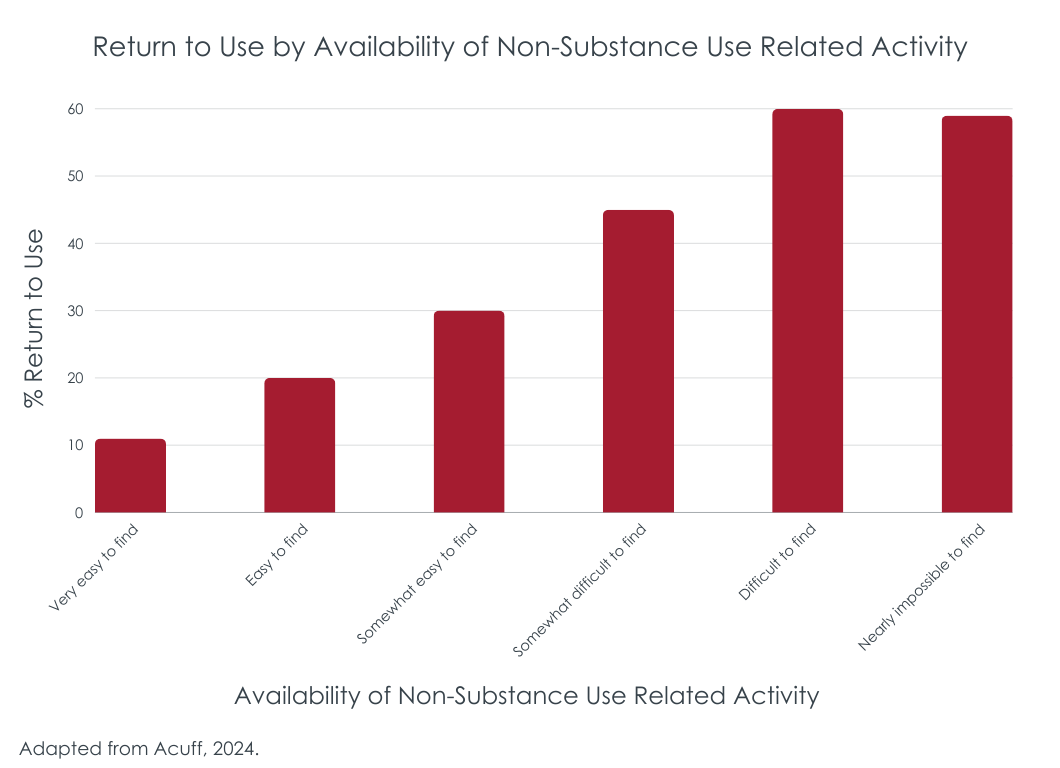

After statistically controlling for demographic characteristics as well as sleep disturbance, inability to feel pleasure (i.e., anhedonia), and stress, greater access to fun activities was associated with lower odds of returning to substance use. Notably, for every additional point on the 1-6 scale of access to fun activities, participants had 32% greater odds of not returning to substance use.

Similarly, after statistically controlling for the same demographic and individual characteristics, greater enjoyment of fun activities was also associated with lower odds of returning to substance use. For every additional point on the 1-6 scale of enjoyment of fun activities, participants had 38% greater odds of not returning to substance use.

Greater access to, and enjoyability of, fun activities associated with life satisfaction

Participants who endorsed more time spent in fun activities versus time spent in substance use related activities reported greater life satisfaction, with a large effect size.

Additionally, after statistically controlling for demographic characteristics in the full sample, greater access to fun activities, as well as enjoyment of fun activities, were both associated with notably greater life satisfaction. These relationships were also observed when just considering those who returned to substance use.

Finally, in a single model considering all study measures together, greater proportion of non-drug related activities relative to drug-related activities, greater access to fun activities, and greater enjoyment of fun activities were each related to greater life satisfaction. As might be expected, the degree to which individuals enjoyed fun activities was associated with the largest effect on life satisfaction.

The researchers’ findings provide evidence of a link between access to fun activities and substance use outcomes and life satisfaction in individuals in early recovery from substance use disorder. Though the observed relationships were robust, caution should be exercised in interpreting these findings because these data were collected at a single point in time (i.e., they were cross-sectional). It cannot be known for sure if access to fun activities directly affects odds of return to substance use. It is possible that there was a third, unmeasured factor that was driving the observed relationships. Additionally, there’s a significant risk for bias in these results, as individuals doing well following discharge from treatment would be more likely to have participated in the study survey. Individuals not doing well and who had perhaps experienced substance use disorder relapse may be less well represented in these findings. As such, these results may not accurately reflect associations between access to fun activities, substance use, and life satisfaction across the breadth of individuals leaving substance use disorder treatment.

At the same time, results are consistent with previous research indicating that fun activities can compete with substance use for attention and reduce the likelihood individuals will engage in substance use among individuals wishing to reduce or stop their substance use. These findings are novel in their focus on early recovery from substance use disorder. This is important for a number of reasons. It suggests that even for individuals with an extensive history of over-learned substance use behaviors, alternative ‘reinforcers’ like fun activities might still have the potential to influence behavior in beneficial ways. Additionally, these findings highlight the importance of external and social resources in substance use disorder recovery, reinforcing the idea that helping individuals accrue resources (i.e., recovery capital) may enhance substance use disorder treatment and recovery planning.

The researchers’ findings are also notable for the observed differences in access to fun activities between participants whose primary substance was alcohol, versus drugs such as methamphetamine and heroin. It can’t be known from these data why this is, but it’s likely this effect is at least in part explained by the particular stigmatization of people who use these drugs, and the social marginalization that results. Such individuals seeking substance use disorder recovery might especially benefit from help accessing fun activities and other related forms of recovery capital.

Participants whose primary substance was methamphetamine, marijuana, or heroin also endorsed less enjoyment of fun activities relative to those for whom alcohol was primary. This might be related to the nature and quality of fun activities to which these groups have access.

Access to fun activities may protect against return to substance use in early substance use disorder recovery and increase life satisfaction. Increasing access to fun activities through treatment programs and social initiatives will likely confer benefit to people seeking recovery. People whose primary substance is methamphetamine or heroin appear to have particularly limited access to fun activities relative to those for whom alcohol is primary and may especially benefit from such initiatives.

Acuff, S. F., Ellis, J. D., Rabinowitz, J. A., Hochheimer, M., Hobelmann, J. G., Huhn, A. S., & Strickland, J. C. (2024). A brief measure of non-drug reinforcement: Association with treatment outcomes during initial substance use recovery. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 256, 111092. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2024.111092

l

Alcohol and other drugs produce effects that are rewarding to the individual taking them. Not surprisingly, the rewarding nature of alcohol and other drugs is amplified when individuals’ lack alternative rewarding activities. Conversely, people with greater access to rewarding, fun activities are less likely to develop substance use disorders and related problems.

In theory, access to rewarding, fun activities would also be protective in people engaged in treatment for substance use disorder. This fits with contemporary theories of addiction recovery that recognize the importance of recovery capital – the sum of tangible and intangible resources available to an individual. It also fits with research showing the importance of changes in social networks from pro-substance-using to pro-recovery peers, which is likely also associated with greater access to pleasurable activities not involving alcohol and other drugs. Thus, access to fun activities may support substance use disorder recovery, yet its influence on recovery outcomes has not been well studied.

In this study, researchers explored how access to fun activities, and the enjoyment derived from them, is associated with substance use outcomes and life satisfaction in a large sample of people in treatment for substance use disorder.

This was an observational study of 5,481 individuals who had recently completed treatment for substance use disorder and were assessed 30 days following treatment discharge to explore associations between access to fun activities and return to substance use and life satisfaction.

Data were collected using a web-based platform delivered via email or text message, with participants asked to characterize their past 30 days since leaving treatment. Measures included: 1) Time (hours per week) spent in fun activities versus substance use related activities; 2) Access to fun activities (on a scale from 1-6); 3) Enjoyability of fun activities (on a scale from 1-6).

The primary study outcomes measured for the 30 days following treatment discharge were: 1) Return to any substance use, including any alcohol or other drugs (yes or no); and 2) perceived life satisfaction (on a scale of 1-10). Study participants identified their primary drug at treatment intake.

The study sample was 62% male, 37% female, and <1% Other. The majority of participants were White (85%), with individuals identifying as African American (7%), Native American (1%), Asian (1%), and Other (5%) also represented, but to a much lesser degree.

Access to, and enjoyability of fun activities varied by primary substance

Participants whose primary substance was alcohol had the greatest time spent in fun activities relative to time spent in substance use related activities. This was in contrast to participants whose primary substance was benzodiazepines, cocaine, heroin, marijuana, methamphetamine, prescription opioids, or prescription stimulants.

In terms of access to fun activities, participants reporting methamphetamine as primary reported less access relative to participants whose primary substance was alcohol. Additionally, when just considering the 1,369 participants who had returned to substance use over the assessment period, those whose primary substances were either methamphetamine or heroin reported less access to fun activities relative to those for whom alcohol was primary, with medium-sized differences. Specifically, in this sub-sample who returned to any use, heroin-primary individuals had 60% of their free time spent on fun activities versus 75% of alcohol-primary individuals.

There were also differences in terms of enjoyment of fun activities. Relative to participants whose primary substance was alcohol, participants reporting marijuana or methamphetamine as primary reported less enjoyment of fun activities. And among participants who had returned to substance use, those whose primary substances were either methamphetamine or heroin reported less enjoyment of fun activities relative to those for whom alcohol was primary.

Greater access to, and enjoyability of, fun activities associated with lower chance of substance use

After statistically controlling for demographic characteristics as well as sleep disturbance, inability to feel pleasure (i.e., anhedonia), and stress, greater access to fun activities was associated with lower odds of returning to substance use. Notably, for every additional point on the 1-6 scale of access to fun activities, participants had 32% greater odds of not returning to substance use.

Similarly, after statistically controlling for the same demographic and individual characteristics, greater enjoyment of fun activities was also associated with lower odds of returning to substance use. For every additional point on the 1-6 scale of enjoyment of fun activities, participants had 38% greater odds of not returning to substance use.

Greater access to, and enjoyability of, fun activities associated with life satisfaction

Participants who endorsed more time spent in fun activities versus time spent in substance use related activities reported greater life satisfaction, with a large effect size.

Additionally, after statistically controlling for demographic characteristics in the full sample, greater access to fun activities, as well as enjoyment of fun activities, were both associated with notably greater life satisfaction. These relationships were also observed when just considering those who returned to substance use.

Finally, in a single model considering all study measures together, greater proportion of non-drug related activities relative to drug-related activities, greater access to fun activities, and greater enjoyment of fun activities were each related to greater life satisfaction. As might be expected, the degree to which individuals enjoyed fun activities was associated with the largest effect on life satisfaction.

The researchers’ findings provide evidence of a link between access to fun activities and substance use outcomes and life satisfaction in individuals in early recovery from substance use disorder. Though the observed relationships were robust, caution should be exercised in interpreting these findings because these data were collected at a single point in time (i.e., they were cross-sectional). It cannot be known for sure if access to fun activities directly affects odds of return to substance use. It is possible that there was a third, unmeasured factor that was driving the observed relationships. Additionally, there’s a significant risk for bias in these results, as individuals doing well following discharge from treatment would be more likely to have participated in the study survey. Individuals not doing well and who had perhaps experienced substance use disorder relapse may be less well represented in these findings. As such, these results may not accurately reflect associations between access to fun activities, substance use, and life satisfaction across the breadth of individuals leaving substance use disorder treatment.

At the same time, results are consistent with previous research indicating that fun activities can compete with substance use for attention and reduce the likelihood individuals will engage in substance use among individuals wishing to reduce or stop their substance use. These findings are novel in their focus on early recovery from substance use disorder. This is important for a number of reasons. It suggests that even for individuals with an extensive history of over-learned substance use behaviors, alternative ‘reinforcers’ like fun activities might still have the potential to influence behavior in beneficial ways. Additionally, these findings highlight the importance of external and social resources in substance use disorder recovery, reinforcing the idea that helping individuals accrue resources (i.e., recovery capital) may enhance substance use disorder treatment and recovery planning.

The researchers’ findings are also notable for the observed differences in access to fun activities between participants whose primary substance was alcohol, versus drugs such as methamphetamine and heroin. It can’t be known from these data why this is, but it’s likely this effect is at least in part explained by the particular stigmatization of people who use these drugs, and the social marginalization that results. Such individuals seeking substance use disorder recovery might especially benefit from help accessing fun activities and other related forms of recovery capital.

Participants whose primary substance was methamphetamine, marijuana, or heroin also endorsed less enjoyment of fun activities relative to those for whom alcohol was primary. This might be related to the nature and quality of fun activities to which these groups have access.

Access to fun activities may protect against return to substance use in early substance use disorder recovery and increase life satisfaction. Increasing access to fun activities through treatment programs and social initiatives will likely confer benefit to people seeking recovery. People whose primary substance is methamphetamine or heroin appear to have particularly limited access to fun activities relative to those for whom alcohol is primary and may especially benefit from such initiatives.

Acuff, S. F., Ellis, J. D., Rabinowitz, J. A., Hochheimer, M., Hobelmann, J. G., Huhn, A. S., & Strickland, J. C. (2024). A brief measure of non-drug reinforcement: Association with treatment outcomes during initial substance use recovery. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 256, 111092. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2024.111092

l

Alcohol and other drugs produce effects that are rewarding to the individual taking them. Not surprisingly, the rewarding nature of alcohol and other drugs is amplified when individuals’ lack alternative rewarding activities. Conversely, people with greater access to rewarding, fun activities are less likely to develop substance use disorders and related problems.

In theory, access to rewarding, fun activities would also be protective in people engaged in treatment for substance use disorder. This fits with contemporary theories of addiction recovery that recognize the importance of recovery capital – the sum of tangible and intangible resources available to an individual. It also fits with research showing the importance of changes in social networks from pro-substance-using to pro-recovery peers, which is likely also associated with greater access to pleasurable activities not involving alcohol and other drugs. Thus, access to fun activities may support substance use disorder recovery, yet its influence on recovery outcomes has not been well studied.

In this study, researchers explored how access to fun activities, and the enjoyment derived from them, is associated with substance use outcomes and life satisfaction in a large sample of people in treatment for substance use disorder.

This was an observational study of 5,481 individuals who had recently completed treatment for substance use disorder and were assessed 30 days following treatment discharge to explore associations between access to fun activities and return to substance use and life satisfaction.

Data were collected using a web-based platform delivered via email or text message, with participants asked to characterize their past 30 days since leaving treatment. Measures included: 1) Time (hours per week) spent in fun activities versus substance use related activities; 2) Access to fun activities (on a scale from 1-6); 3) Enjoyability of fun activities (on a scale from 1-6).

The primary study outcomes measured for the 30 days following treatment discharge were: 1) Return to any substance use, including any alcohol or other drugs (yes or no); and 2) perceived life satisfaction (on a scale of 1-10). Study participants identified their primary drug at treatment intake.

The study sample was 62% male, 37% female, and <1% Other. The majority of participants were White (85%), with individuals identifying as African American (7%), Native American (1%), Asian (1%), and Other (5%) also represented, but to a much lesser degree.

Access to, and enjoyability of fun activities varied by primary substance

Participants whose primary substance was alcohol had the greatest time spent in fun activities relative to time spent in substance use related activities. This was in contrast to participants whose primary substance was benzodiazepines, cocaine, heroin, marijuana, methamphetamine, prescription opioids, or prescription stimulants.

In terms of access to fun activities, participants reporting methamphetamine as primary reported less access relative to participants whose primary substance was alcohol. Additionally, when just considering the 1,369 participants who had returned to substance use over the assessment period, those whose primary substances were either methamphetamine or heroin reported less access to fun activities relative to those for whom alcohol was primary, with medium-sized differences. Specifically, in this sub-sample who returned to any use, heroin-primary individuals had 60% of their free time spent on fun activities versus 75% of alcohol-primary individuals.

There were also differences in terms of enjoyment of fun activities. Relative to participants whose primary substance was alcohol, participants reporting marijuana or methamphetamine as primary reported less enjoyment of fun activities. And among participants who had returned to substance use, those whose primary substances were either methamphetamine or heroin reported less enjoyment of fun activities relative to those for whom alcohol was primary.

Greater access to, and enjoyability of, fun activities associated with lower chance of substance use

After statistically controlling for demographic characteristics as well as sleep disturbance, inability to feel pleasure (i.e., anhedonia), and stress, greater access to fun activities was associated with lower odds of returning to substance use. Notably, for every additional point on the 1-6 scale of access to fun activities, participants had 32% greater odds of not returning to substance use.

Similarly, after statistically controlling for the same demographic and individual characteristics, greater enjoyment of fun activities was also associated with lower odds of returning to substance use. For every additional point on the 1-6 scale of enjoyment of fun activities, participants had 38% greater odds of not returning to substance use.

Greater access to, and enjoyability of, fun activities associated with life satisfaction

Participants who endorsed more time spent in fun activities versus time spent in substance use related activities reported greater life satisfaction, with a large effect size.

Additionally, after statistically controlling for demographic characteristics in the full sample, greater access to fun activities, as well as enjoyment of fun activities, were both associated with notably greater life satisfaction. These relationships were also observed when just considering those who returned to substance use.

Finally, in a single model considering all study measures together, greater proportion of non-drug related activities relative to drug-related activities, greater access to fun activities, and greater enjoyment of fun activities were each related to greater life satisfaction. As might be expected, the degree to which individuals enjoyed fun activities was associated with the largest effect on life satisfaction.

The researchers’ findings provide evidence of a link between access to fun activities and substance use outcomes and life satisfaction in individuals in early recovery from substance use disorder. Though the observed relationships were robust, caution should be exercised in interpreting these findings because these data were collected at a single point in time (i.e., they were cross-sectional). It cannot be known for sure if access to fun activities directly affects odds of return to substance use. It is possible that there was a third, unmeasured factor that was driving the observed relationships. Additionally, there’s a significant risk for bias in these results, as individuals doing well following discharge from treatment would be more likely to have participated in the study survey. Individuals not doing well and who had perhaps experienced substance use disorder relapse may be less well represented in these findings. As such, these results may not accurately reflect associations between access to fun activities, substance use, and life satisfaction across the breadth of individuals leaving substance use disorder treatment.

At the same time, results are consistent with previous research indicating that fun activities can compete with substance use for attention and reduce the likelihood individuals will engage in substance use among individuals wishing to reduce or stop their substance use. These findings are novel in their focus on early recovery from substance use disorder. This is important for a number of reasons. It suggests that even for individuals with an extensive history of over-learned substance use behaviors, alternative ‘reinforcers’ like fun activities might still have the potential to influence behavior in beneficial ways. Additionally, these findings highlight the importance of external and social resources in substance use disorder recovery, reinforcing the idea that helping individuals accrue resources (i.e., recovery capital) may enhance substance use disorder treatment and recovery planning.

The researchers’ findings are also notable for the observed differences in access to fun activities between participants whose primary substance was alcohol, versus drugs such as methamphetamine and heroin. It can’t be known from these data why this is, but it’s likely this effect is at least in part explained by the particular stigmatization of people who use these drugs, and the social marginalization that results. Such individuals seeking substance use disorder recovery might especially benefit from help accessing fun activities and other related forms of recovery capital.

Participants whose primary substance was methamphetamine, marijuana, or heroin also endorsed less enjoyment of fun activities relative to those for whom alcohol was primary. This might be related to the nature and quality of fun activities to which these groups have access.

Access to fun activities may protect against return to substance use in early substance use disorder recovery and increase life satisfaction. Increasing access to fun activities through treatment programs and social initiatives will likely confer benefit to people seeking recovery. People whose primary substance is methamphetamine or heroin appear to have particularly limited access to fun activities relative to those for whom alcohol is primary and may especially benefit from such initiatives.

Acuff, S. F., Ellis, J. D., Rabinowitz, J. A., Hochheimer, M., Hobelmann, J. G., Huhn, A. S., & Strickland, J. C. (2024). A brief measure of non-drug reinforcement: Association with treatment outcomes during initial substance use recovery. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 256, 111092. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2024.111092