Stopping and Starting: Substance Use During and After Pregnancy

Newly pregnant women who use a variety of substances are largely successful in achieving abstinence prior to the last few months of pregnancy. However, the vast majority resume substance use in the first 2 years postpartum, making relapse almost as common as abstinence for this population.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Substance use is common in reproductive age women (30% have problematic alcohol use, 25% smoke cigarettes, and 11% use illicit substances; SAMHSA 2013 Survey results). While it is generally appreciated that pregnancy is a strong motivator for abstinence from these substances, and there are generally high rates of abstinence achieved (greater than 50%) there is little data to show whether abstinence is maintained postpartum. This study focuses on cigarette, alcohol, cannabis and cocaine use during pregnancy and up to two years after delivery.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study is based on data collected as part of a randomized controlled study comparing the effectiveness of psychological treatments for substance use disorders in pregnancy (Psychosocial Research to Improve Drug Treatment in Pregnancy trial).

- READ MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

Data was gathered between 2006-2012 at outpatient clinics in New Haven from pregnant women enrolled prior to the 28th week of pregnancy who reported use of alcohol or illicit substances in the past month (and scored 3+ on the 5 point scale to assess problematic use by the TWEAK measure). Substance use is defined as five or more cigarettes per day; seven drinks per week or three or more per day; any marijuana or any cocaine use in the six months prior to pregnancy.

Only 33% of the study participants met criteria for DSM-IV substance abuse or dependence suggesting that while all were using substances only a minority were using enough to cause significant impairment or distress. Data collected from the 152 female participants in this study includes substance use self-reports as well as toxicology screens (i.e., “drug tests”) during the pregnancy and at three, 12 and 24 months after delivery.

Abstinence and relapse rates for nicotine, alcohol, cannabis and cocaine are the focus of this study, with abstinence defined as one month substance-free just prior to delivery. Since the parent study focused on assessing substance use treatments in pregnancy, the participants received either brief advice or motivational enhancement treatment + cognitive behavior treatment (MET-CBT) during pregnancy with two sessions post-partum.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

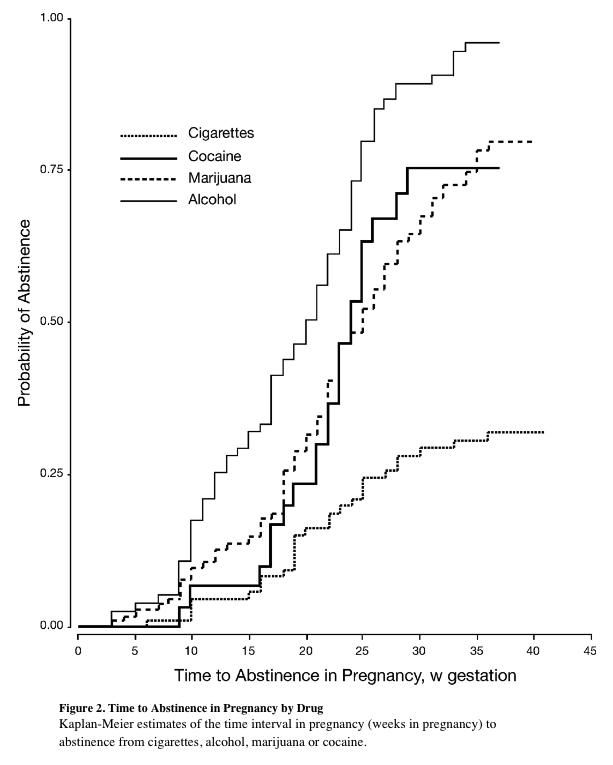

During pregnancy, most women (83%) were able to become abstinent from at least one substance, although, on average, it took greater than four months to achieve that abstinence. 126 of the 152 pregnant women had stopped using at least one of the four substances tracked for the month prior to delivery, and had generally stopped using that substance by the second trimester. The average time it took to achieve abstinence was greater than four months for all four substances analyzed in this study (average of 132 days for alcohol, 146 days for cigarettes, 149 days for cocaine and 152 days for cannabis).

Abstinence rates were highest for alcohol and lowest for cigarettes. Only 30% of cigarette smokers had quit by the final month of pregnancy, whereas 75% of cocaine or cannabis users had stopped their use and more than 90% of alcohol users (eight or more drinks per week or four or more drinks in one day) were able to stop drinking prior to that last month of pregnancy.

Relapse rates are high (80%) during the first year post-partum. Though the average return to use for cigarettes, cannabis, and alcohol was three to five months postpartum, return to cocaine use occurred on average nine to ten months post-partum. In addition to taking longer to resume use, cocaine had the highest sustained abstinence rate (40%) of the four substances analyzed. For alcohol and cannabis, only 10% of the women remained abstinent by 24 months post-partum, with similar findings for cigarette smokers.

The majority (65%) of study participants were using more than one substance, with the combination of cigarettes and marijuana, or cigarettes and alcohol being the most common. Only six subjects were using all four substances concurrently.

Those with substance use disorder and psychiatric diagnoses achieved abstinence and relapses at essentially the same rates as the others. There were no associations between psychiatric diagnoses and abstinence rates, although women with depression had a slightly increased risk of relapse (89% vs 80%).

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Pregnant women are, by and large, able to obtain abstinence during pregnancy from alcohol, cannabis and cocaine (with lower rates for cigarettes). However, it takes on average more than a trimester to achieve that abstinence. Despite the high rates of abstinence obtained, by two years after delivery, virtually all had resumed their substance use. This suggests that pregnancy is a strong motivator for abstinence but that once the baby is born, substance use is gradually resumed at essentially the same rates of use (with the exception of cocaine users, where only 60% resume use during those first 24 months post-partum).

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Although the study analyzed data regarding cigarette smoking as well as alcohol, cannabis and cocaine, the entry criteria for the parent study was alcohol or illicit substance use in the past month. Thus, the conclusions drawn around cigarette smoking apply only for women who smoke in addition to using alcohol, cannabis or cocaine.

- The data presented here was drawn from a prior study which tested the effects of adding MET-CBT (motivational enhancement treatment + cognitive behavior treatment). The data presented in this study combines all of the participants, those having received MET-CBT (who had slightly higher rates of abstinence) together with those who had not received the intervention.

- The women entered the study over a broad range of gestational ages (from six to 36 weeks of pregnancy) which complicates the analysis as four weeks prior to delivery is the cutoff for achieving abstinence.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: There are high rates of success for achieving abstinence during pregnancy. However, it seems to take more than a trimester to achieve abstinence, and a minority of women cannot achieve that goal. Once abstinence is achieved and the baby is born, there may be insufficient supports or motivation to maintain abstinence, with substance use resuming close to pre-pregnancy levels. Increasing treatment or continuing to prioritize abstinence during the stressful post-partum period may help women succeed at staying abstinence, which particularly important for those with a substance use disorder

- For scientists: Given the length of time it takes to achieve abstinence (greater than four months), a critical window in early development has already passed. For the 30-40% of women using substances just prior to becoming pregnant, quitting very early in gestation may have the biggest protective impact on the fetus given that early embryonic development is more sensitive to disruption than the later gestational months. Developing resources and studying interventions to quicken the time to abstinence in newly pregnant women may have a sustained multi-generational impact. The use of contingency management has been shown to achieve more rapid rates of abstinence and could be implemented more widely in these cases.

- For policy makers: There is an important opportunity to help new mothers maintain abstinence from substances. Given the many competing priorities of new motherhood with an understandable decrease in maternal self-care, systems should be put in place to monitor and encourage sustained abstinence. The public health awareness campaign around postpartum depression could serve as a model for this effort, and similarly, the message could come from pediatricians and those involved in caring for young children. An important opportunity for relapse prevention is currently being missed.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: More resources should be devoted to helping new mothers remain abstinent given that they have already overcome an important barrier by stopping substance use, motivated by pregnancy. Targeting or integrating treatment into venues where new mothers are engaged in care already (pediatricians offices, child care venues, parenting groups) may help improve outcomes for this critically important group of substance users whose use impacts the health of young individuals. Being aware of women’s vulnerability to resuming use in the first years postpartum should alert treatment teams to increase resources focused on maintaining abstinence for this group.